Algocult: Identifying with the Algorithm

How much does the internet tell you who you are?

I’m writing weekly dispatches about technology reshaping the ways we create and consume culture. If you like this essay, please hit the heart button above! It helps me reach more readers. And subscribe below:

The writer, editor, actress, and onetime fashion blogger Tavi Gevinson, one of the few people who actually deserve the title of online influencer, wrote a cover story for New York Magazine about Instagram’s impact on her life. She wouldn’t be who she is without it — social media has brought her fame, income, a sponsored Brooklyn apartment, and a need to carefully regulate her public and private personae.

What was interesting to me about this essay was the way that Gevinson talked about Instagram, the language with which she described it. She didn’t depict it as a tool that she used or a space in which she published, but instead a kind of world in itself, that mirrored, imperfectly, the her daily reality, or at least her perception of herself.

Instagram, which gets conflated with “the algorithm” that controls which content gets surfaced most often and becomes most popular, is inseparable from her sense of self. She presents the non-digital self as pure, organic, while the online self is some combination of human and technological, a chimaera: “I can try to imagine an alternate universe where I’ve always roamed free and Instagram-less in pastures untouched by the algorithm. But I can’t imagine who that person is inside,” she wrote.

Part of Gevinson’s solution is to insulate herself from social media, putting a layer between herself and its distortions (I sound like Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, which Gevinson also cites) by having an assistant do the Instagram posting for her. That sounds great, actually! Participate in the digital world, maintain your presence in it, without having to actually interact or invest energy. Maybe we could all just have robots post for us, and then other robots would automate our likes and tell us if there’s anything really important — if someone got a puppy, for example.

Some of the essay’s arguments fall into the category of “digital dualism,” the term Nathan Jurgenson coined in 2011 to denote the (misguided) idea that there is a distinct separation between life online and IRL. The cliche digital dualist complaint is that online interactions aren’t that meaningful, that we can’t have actual friendships or discussions through our screens.

Gevinson positions her online life and the way that The Algorithm filters both what she publishes and what she consumes as something overly mediated, a reflection she came to not recognize. She’s plenty self-aware enough to realize that she has contributed to this problem, but most people can’t escape it so neatly. If Gevinson is using the essay to claim some of her real self back from the internet, the vast majority of us have no recourse; we are — or are at least treated as if we are — what The Algorithm sees us as.

* * *

One concrete example of the division between the digitized self and the blood-and-guts version: A Chinese woman got plastic surgery that made her unrecognizable to face-recognition software. She immediately had trouble shopping online, checking into her job, and boarding trains, because the systems depended on her pre-surgery digitized identity. This is more drastic than Instagram ennui.

* * *

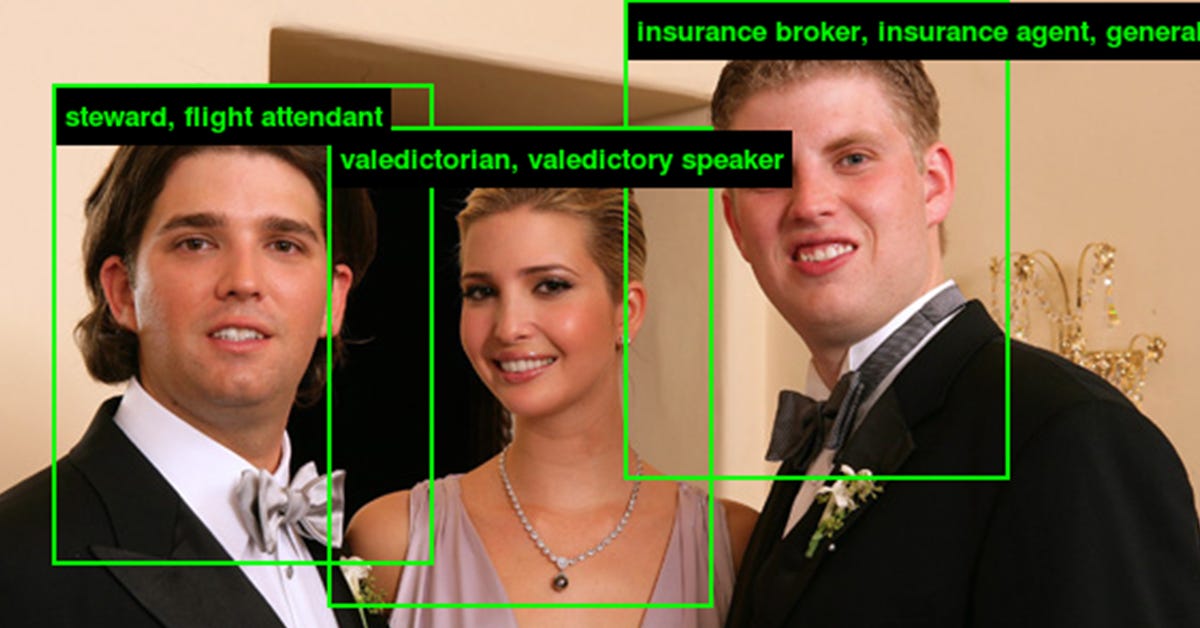

A viral art project further underlined this point. Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen’s ImageNet Roulette (you might recognize the green square from… everywhere online this week) was built on an authoritative database of tagged images, ImageNet, that was begun in 2009 to train AI to recognize objects. Its origins are human — its creators hired Amazon Mechanical Turk workers to tag straightforward images with terms like “apple” but also, apparently, images of people with “debtor,” “snob,” “swinger,” and “slav,” among many other offenses.

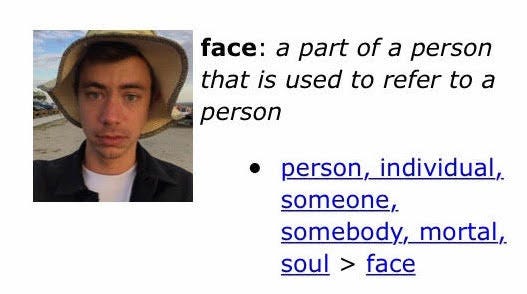

ImageNet Roulette allows you to upload a photo of yourself and have the AI judge you, tagging the image with the terms that it thinks apply. The terms also come with elaborate definitions that sound either poetic or grammatically suspect, drawn from the similar database WordNet. I put in a selfie and got: “face: a part of a person that is used to refer to a person — person, individual, someone, somebody, mortal, soul.” My (bearded) friend Mark got “beard: a person who diverts suspicion from someone (especially a woman who accompanies a male homosexual in order to conceal his homosexuality).”

Somewhere in the dataset this definition was lurking, brought illogically (we think) to the surface. But it had to be put there first. The digital reflection is not neutral: “The whole endeavor of collecting images, categorizing them, and labeling them is itself a form of politics, filled with questions about who gets to decide what images mean and what kinds of social and political work those representations perform,” as Crawford and Paglen write.

ImageNet Roulette went viral because it was funny. We’re amused by how The Algorithm fails to recognize us, mistaking people for objects and vice versa. In the moment of laughing at the labels, we’re secure in our humanity, assuaged that we’re still smarter than the machines. Even if online is just as valid as off, there still isn’t a 1:1 relationship between the two.

But then again, is the self so real in the first place? The more time we spend in algorithmic spaces, the more we come to identify with their distortions.

Other Algocult News

— Amazon’s search function also prioritized its own products, another strike against any perception of neutrality.

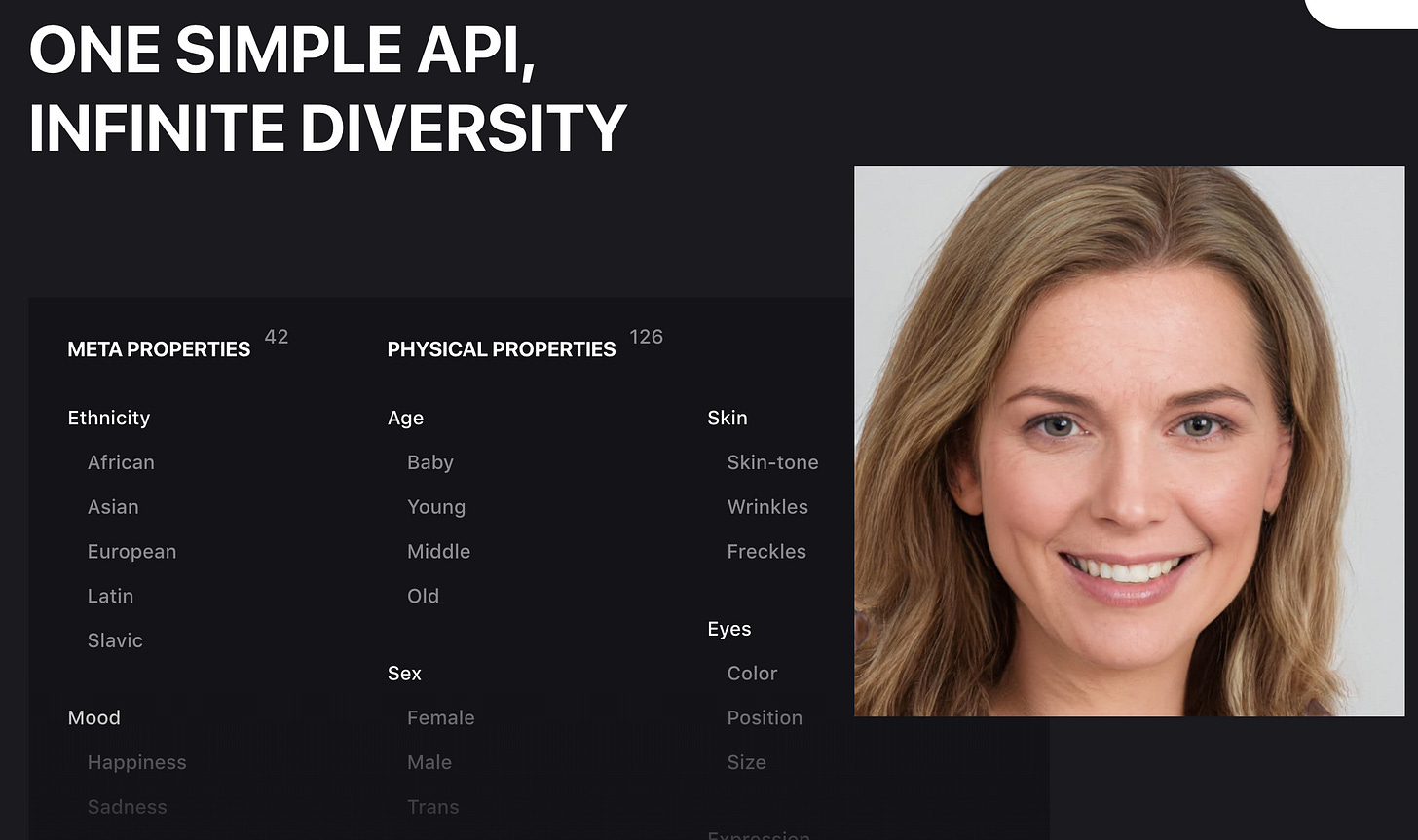

— “Free resource of 100k diverse faces generated by AI”: startup guy generates fake people so either you can mimic diversity on your ‘About Us’ page or, do as he plans to and create an “AI model agency.” The faces are mostly uncanny valley nightmares but the dystopia is real.

— Podcast tool Descript comes with Overdub, a feature that lets you synthesize your own voice reading words that you only type. It’s kind of like the autotune of speech but could also easily be very dystopian! I am interested in this kind of “faked” art or media.

— Charlie XCX on how the structure of streaming platforms changes songwriting. There’s “no difference between a mixtape and an album” and fewer gatekeepers, but optimizing for streaming revenue means a very specific style of song: immediate chorus, no introduction, hook at the top.

If you like this essay, please hit the heart button below! It helps me reach more readers. Email me any thoughts or things you’d like me to look into and subscribe here.

— Follow me on Twitter

— Preorder my book on minimalism, The Longing for Less

— Read more of my writing: kylechayka.com