Essay: Minimalism, between art and life

Notes for a talk, & TLFL paperback.

Hello, I’m Kyle Chayka, a staff writer for The New Yorker, on Twitter / Threads, and author of the forthcoming book Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture. This is my personal newsletter, where I share my columns and publish original essays. Subscribe here.

I have two announcements: First, if you or your friends or family are in Houston, Texas, I am giving a talk at The Menil Collection, a fantastic art museum, this Wednesday at 7 PM — free and open to anyone. The talk is called “Minimalism, Between Art and Life,” and it stems from my first book The Longing for Less while also responding to the museum’s show of the minimalist and conceptualist Hanne Darboven. Some notes toward that talk are below in this newsletter. Please do pass on the link to anyone who might be able to make it!

Second, speaking of that book, the new paperback of The Longing for Less will be out from Bloomsbury on January 9! You’ll be able to find it in bookstores and online. It has a lovely new paperback cover:

It’s been four years since that book came out, and my next book, Filterworld, is out January 16. (Pre-order it!) It’s a nice moment to look back on some of those themes. One nice thing about writing a book is that after it’s done, you’ve thought through all of your thoughts about a subject. It’s like a sculpture that you never have to carve again; it just rests there, the work completed. But it lives on as (hopefully) more and more people read it.

Essay: Minimalism, Between Art and Life

Minimalism is an art movement that became a lifestyle. The first proper Minimalists — capital-M, you might label them — were artists in downtown Manhattan in the 1960s who reclassified industrial materials as art objects. These were people like Donald Judd, who turned factory-made aluminum boxes into sculptures (“specific objects,” he called them), and Dan Flavin, who did the same with fluorescent light bulbs. Other artists who were drafted, usually against their will, into the Minimalist label made art that looked as simple as possible. They adopted the stark austerity of the industrial — like Sol LeWitt’s geometric wall drawings or Agnes Martin’s square canvases of only a few stripes or a grid.

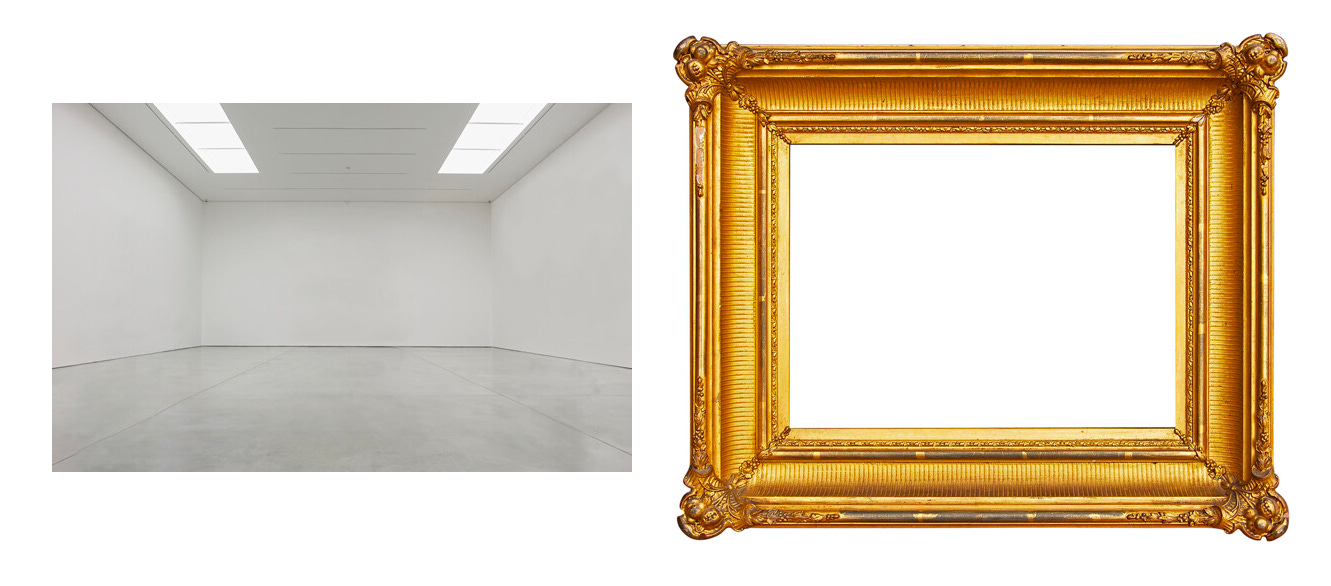

That transformation was something like changing the stuff of life — mundane infrastructure, detritus — into the stuff of art. Minimalism was an act of recontextualization. When encountering a Judd, you have to experience the aluminum box as art in the same way you would a Michelangelo marble. The artists were helped along in that process by the invention of the “white cube”: the blank empty box that we all now know as the archetype of gallery or museum architecture. The white cube reinforces the idea that anything that resides within it is art, much as how an elaborate gilt frame marked a portrait on canvas as important in the 19th century. You don’t have to figure out if the fluorescent light bulb mounted on the wall is art or just lighting; the gallery space tells you that it’s art. (It doesn’t always work: I once saw a crumpled cup on the desk-side ledge of a gallery in DUMBO. I thought it was trash, but it was an intricately constructed trompe-l’oeil sculpture made to look like trash.)

But a funny thing happened over the decades. The strategy of Minimalist art in the white cube was applied to other things. Fashion boutiques took it on, building empty stores that proclaimed the idea that their luxury bags and shoes were art, too. Then it was the vocabulary of residential architecture, with endless empty condos that mimicked the factory lofts that the original Minimalist artists lived in. Did that mean the human life inside the white-cube apartment was the art? The aesthetic of minimalism became separated from its original insight, which is that what we overlooked could be art, too. What was once radical became fetishized, a fossilized style. Which, of course, is always happening to the avant-garde.

In 1959, the artist Robert Rauschenberg wrote in a statement about his work, “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two)” Rauschenberg isn’t usually classified as a Minimalist — perhaps his work is too visually maximalist — but he performed a similar trick, turning newspaper fragments, cardboard, and screenprints into transcendent painting-sculptures. Another time, he recast the line: “You can’t make either life or art, you have to work in the hole in between, which is undefined.” Minimalism, I think, was particularly successful in operating in that oft-mentioned gap between art and life. It shuttled between the two, functioning on both levels, providing both a way to see the world and the objects with which to populate it. Modernism created industrial space; minimalism showed us how to live in it.

The avant-garde can’t survive popularity. Minimalist art itself is still radical — it’s not particularly appreciated by viewers nor by collectors (at least not as much as vintage Abstract Expressionism or the contemporary figurative painting revival). Yet the style is everywhere, dulled into banality. I think that’s because the Minimalist artists were early to recognize the fact that for many more people beyond the Manhattan creative elite, life was becoming art, and vice versa. Life is now a performance in the white cube — of the empty apartment, or of the Instagram photo frame or the TikTok video backdrop that makes use of a white wall’s visual clarity. When we fetishize everything as art, we don’t need that original art object quite as much.

What is often missed about the Minimalist artists is that they lived in different ways, too. They inhabited the world in a different way; they constructed their own environments and routines, developing ways to structure space or time into patterns that they found more beautiful. Judd moved to Marfa, Texas, and carved gracious living spaces out of defunct desert infrastructure. Agnes Martin moved to New Mexico and drove cars fast. Casting a wider net, we can look to On Kawara’s minimalist paintings of dates, simple numbers on monochrome, and his postcards reading “I am still alive,” which he sent to friends and art dealers. Or Tehching Hsieh’s arduous durational performances, which consisted of following repetitive or restrictive commandments. For his “Art / Life: One Year Performance 1983–1984 (Rope Piece),” Hsieh physically tied himself to the artist Linda Montano for a full year, 24/7. Hanne Darboven cocooned herself in her family home in Hamburg for decades and stocked its rooms with scattered artifacts of the twentieth century, which she enclosed in vitrines and surrounded by her minimalist drawings that transcribe dates and numerical patterns.

Minimalism is perhaps the process of translating between art and life, of determining what the gesture will be that connects them. It doesn’t just happen in the studio. It happens in the home, while traveling, out in the world. It can happen anywhere, because it isn’t defined by a particular visual outcome. Like one of Flavin’s fluorescent bulbs, it exists in plain sight for the viewer, an encounter with the unfamiliar that challenges us to change how we perceive our surroundings.

Is there a UK publication date for the The Longing for Less paperback?