Welcome to my personal newsletter. I’m publishing weekly-ish essays on digital technology and culture, in the run-up to my January 2024 book FILTERWORLD: How Algorithms Flattened Culture. Subscribe or read the archive here.

My new book Filterworld is making its way out into the world in iterations. Its current state is a PDF, complete with the cover and some descriptive copy, like a shadow of the physical object. One day, I opened a standard-looking book package from my apartment hallway (I get sent a lot of books) and it was not someone else’s book, but my book! It was a single bound galley that I could hold in my hands, which suddenly made it feel much more real. I love PDFs — you can search in them, you can email them instantly, they float around the internet — but interacting with a physical book is different. The act of flipping through it is, as far as I can think, unmatched in digital experience.

My book is so much about how technology dictates culture. The devices that we use aren’t just accessories to culture or windows that we consume things through; they are collaborators, gateways, and molds. “The medium is the message,” as McLuhan wrote, is another version of this idea — or at least that the medium is inextricable from the meaning. My latest column for The New Yorker brought it up, too. I reviewed Laine Nooney’s book Apple II Age about “personal computers” and the evolution of the idea that computers belong in the home, on an individual desktop. That wasn’t inevitable; the idea of a personal computer had to be invented, manufactured, and marketed. We had to imagine computers as personal machines.

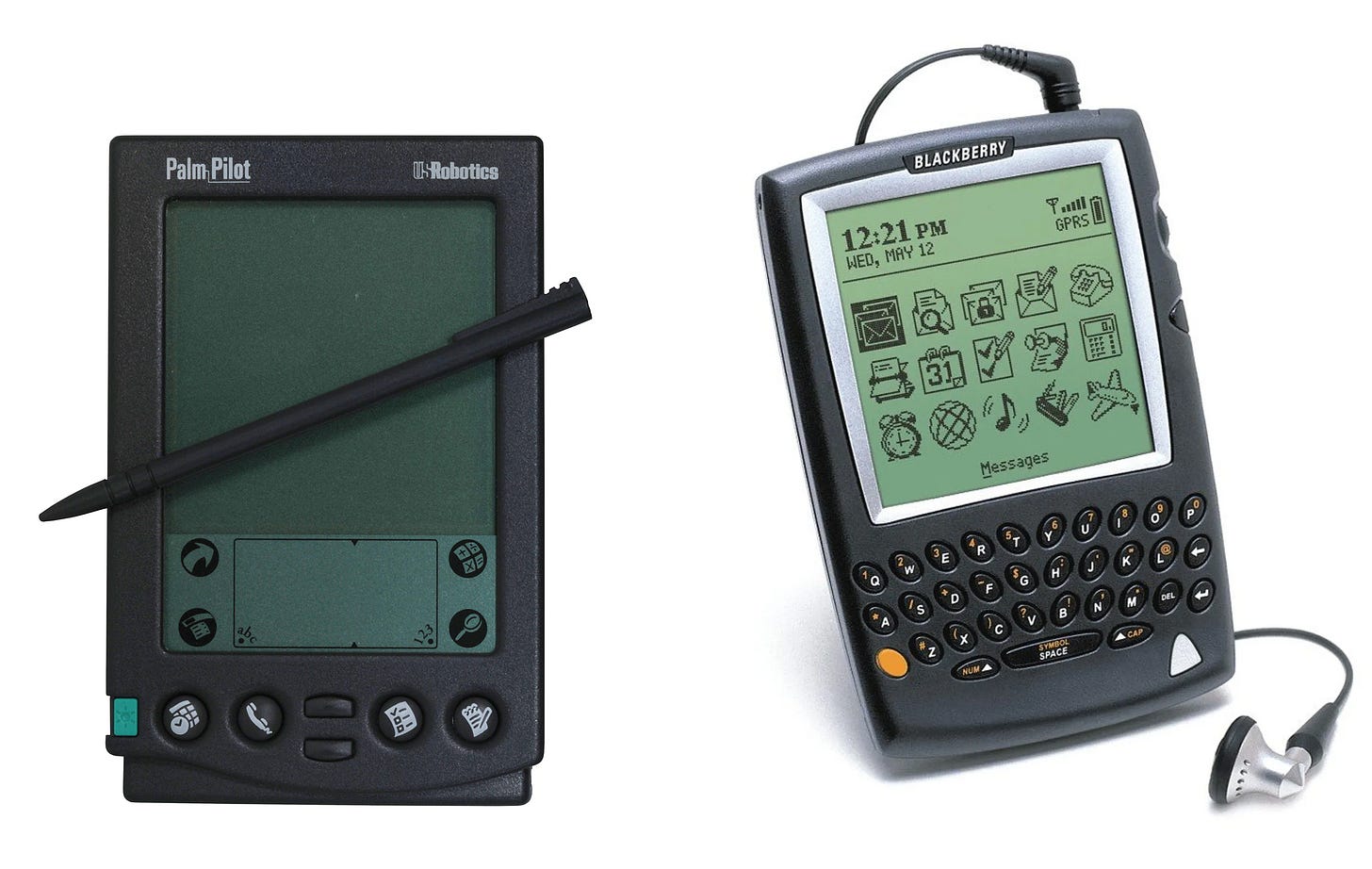

That happened in the 1970s and ‘80s, before I was born. The process that I experienced in the ‘90s and 2000s was the popularization of the portable computer, a handheld device that could do all the things a desktop computer could. Palm Pilots came out in 1997 and the first BlackBerry in 1999. I remember wanting one of these devices even as a 12-year-old, when I would have had no use for the kind of calendar planning and to-do list making that made up most of its functions. Boring, adult stuff! The devices were clunky, their screens were plasticky, and they used styluses. But still there was this ineffable appeal to holding a gateway to a digital world in your hand — though I don’t think I could even conceptualize getting the internet on a portable device at the time, since this was the era of dial-up.

In 2004 or so my parents got me a Palm Pilot-esque device to play around with. It had a few buttons, a stylus hidden in the top, and a slide-out full keyboard — a messy, chunky thing in shiny, gray plastic. I remember mostly messing around with the firmware, trying to modify it so I could install emulators to play video games. The screen would fill with inscrutable command-line text that my feeble programming skills balked at. The games worked — barely. But I got an epic sense of agency from being able to carry around and modify this personal, digital tool. I still remember the awe I got from the gleaming glass screen that I could carry around and put in my pocket. (By the time I got my first iPhone in 2010, the very same experiences had become mundane.)

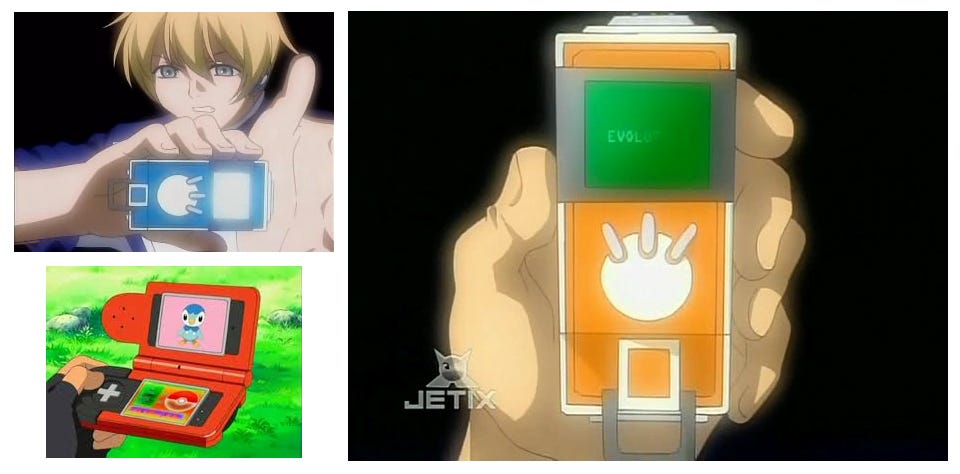

Where did I get that desire from for a computer that was both personal and portable, a little Swiss army knife of technology? Or where did I get my imagined image of it, the subconscious dream that heightened it from a banal scheduling device to something (hypothetically, in the future) life-changing? I think for me it came from anime. I grew up on the Pokemon and Digimon television shows, in that order. Pokemon had its Pokedex, the bright-red flip-phone device that catalogued every creature in the world and displayed maps and charts. Digimon (by far the emotionally deeper show, underrated) had the Digivice, a much more evocative tool that beamed the holder literally into another, virtual universe and helped their pet monsters evolve. The young heroes of these shows got agency from their devices, too — the devices were representations, perhaps, of their control over their own lives and the adventures they were on, something that I desperately wanted. If you had the device, you could do anything, go anywhere.

I collected these images for an essay I proposed to write in 2011 — more than a decade ago, and not long after I had an actual iPhone. The idea has stayed with me ever since; I just dug them up from my Gmail account, another miracle of technology, an infinite personal archive. The screencaps still grip my mind, inspiring a mixture of ‘90s nostalgia and anticipation for a future not yet achieved. Maybe the devices that we ended up with are too flat, too homogenous and standardized. They possess us more than we possess them. Everyone’s iPhones look the same, but the Pokedex and Digivice were unique (as I recall) to each owner. They had funky, geometric forms and garish cases and buttons. They weren’t just flat glass touchscreens.

In that 2011 proposal, I wrote, “What these fantastical, technological objects have in common is their ability to modify carriers’ immediate surroundings, flattening together the actual and the virtual and forming a window from reality into the unreal.” (Sometimes looking back at your old writing is cringey, but it’s obvious I’ve just pursued the same themes ever since…) At the time, I didn’t realize how “the actual and the virtual” were more easily merged than I thought they would be. Where Pokemon and Digimon depicted wholly alternate realities — virtual realms that were fun and cool, lol — the virtual world of today’s devices has simply overlaid the physical like a dense fog.

The iPhone isn’t escapist; maybe it just reinforces the grip of our established, boring, capitalist reality. The iPhone doesn’t present itself as transcendental; it no longer feels like a new way of understanding or engaging with the world. It only refers to itself, its own banal virtual environment, which amounts to a vast storefront. When I look at these decades-old images, the hint of a button or antenna portends more possibility than any app I can download. I want a device that is truly personal, in that it is a reflection of the self (unique, changing, unstable). A device that urges its holder into new, unfamiliar places. That dream of agency is still there, unfulfilled.

Just as I’ve been thinking about this for 12 years, I’m sure I’m not done with the subject. I want to collect more images and write more about the aesthetics of these devices. Please comment or send me screencaps if you have any! Reply or email chaykak@gmail.com. Subscribe to follow along.

There's something to the fact that Pokemon was also a game for the Gameboy, another kind of personal machine.

"They possess us more than we possess them."

Reminds me of Richard Wright “It’s a danger that we could become slaves of all our equipment.”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YhHo_74Hp0